.png)

I get this question almost weekly: "How much cash should I be sitting on once I retire?"

It's a fair concern. You've spent decades building your practice, arguing cases, and accumulating wealth. Now you're staring down retirement, and suddenly that pile of cash feels like the only thing standing between you and financial disaster.

And though hoarding cash can feel comfortable at times–in retirement it can actually work against you.

Think of cash like keeping all your legal briefs in a fireproof safe. Sure, they're protected from immediate danger, but they're not doing any work for you either.

When I talk with lawyers approaching retirement, I often hear the same fear: "What if the market crashes right when I need my money?"

It's a logical concern. You've seen economic downturns before. You remember 2008.

But here's what's counterintuitive: markets tend to rise over time. So that "safety net" of excess cash? It's actually creating a performance drag on your entire portfolio. Your stocks and bonds have to work that much harder to overcome this cash anchor, which can push you toward riskier investments to compensate.

That's the opposite of what you want in retirement.

Before we figure out your cash allocation, we need to understand how your portfolio should work in the first place. And it all starts with one simple question: What do you need to spend each month?

I know, I know. You expected me to ask about Tesla versus Microsoft, or your thoughts on inflation over the next six months. But those feelings don't drive smart allocation decisions.

Your expenses do.

Let's walk through an example. Say you need $12,000 monthly for all your expenses. Social Security covers $5,000 of that, which means your portfolio needs to generate the remaining $7,000 each month (adjusted for inflation each year).

Given your total assets, let's assume we determine you need a 6.5% average annual return to sustain these withdrawals. From there, we can look at historical data and determine that a 60% stocks/40% bonds or 70% stocks/30% bonds allocation would be appropriate.

Now we have a clear understanding of the job your portfolio has to undertake.

The key element to observe here is that your allocation shouldn't change every year based on where you think the market is heading. Markets work over the long term, and we can remove the guessing game entirely.

But what about those down market years? You're right to be concerned about selling assets at a loss.

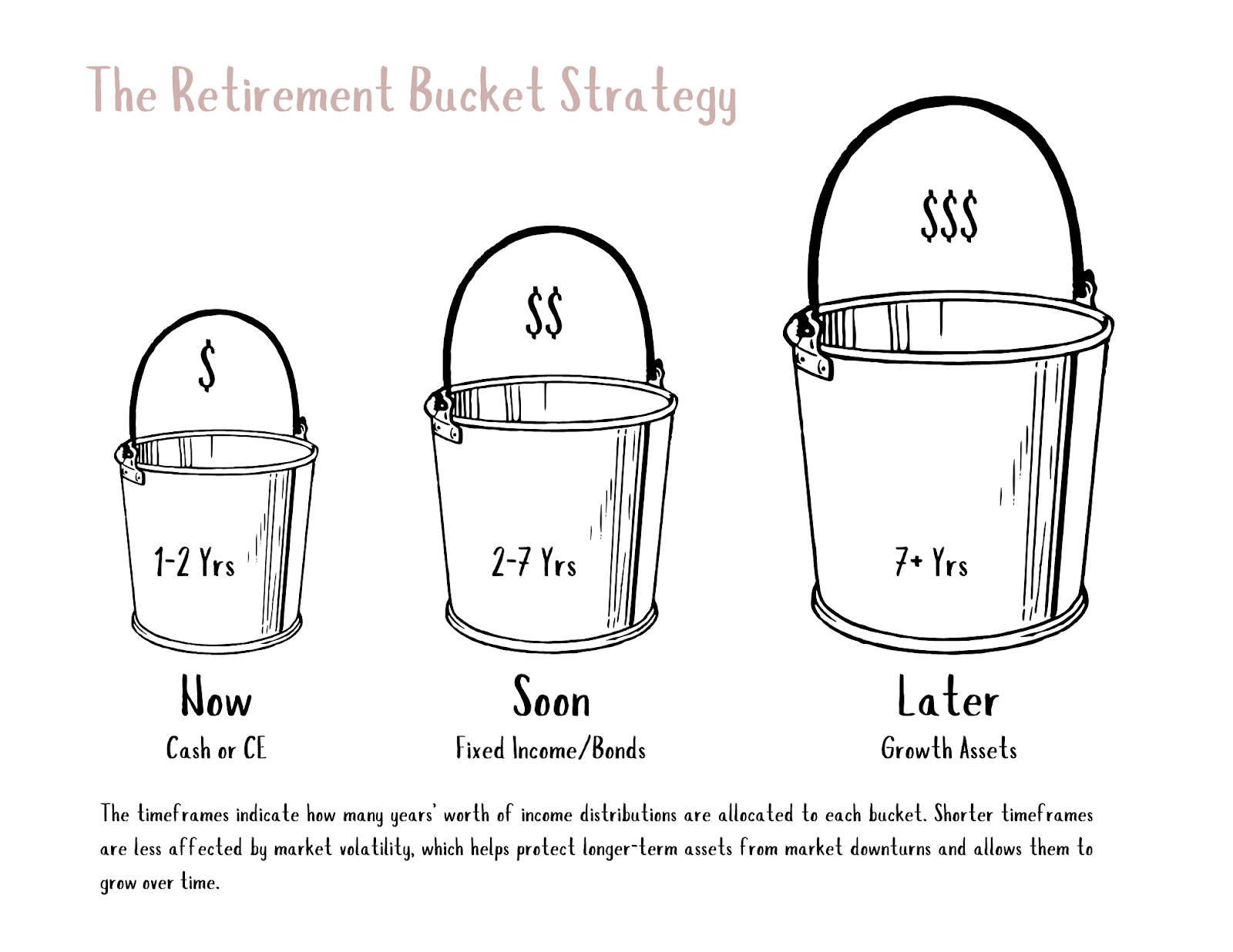

This is where we get strategic about timing. I help my clients build what I call a "war chest" that looks like this:

Cash (money market or high-yield savings): 1-2 years of portfolio withdrawals to insulate against short-term drops in the market.

Bonds: Years 2-7 of portfolio withdrawals designed as next layer or defense with ample time for recovery.

Stocks: Money you won't need for 7+ years. This is the volatile stuff. The S&P 500 type investments. The ones that drive mass hysteria when the market drops. But notice how much time we’re giving for this sleeve to rebound.

Looks like this:

This approach often results in something pretty close to that original 60/40 or 70/30 allocation we calculated based on your expenses. But now we've matched timeframes to when you actually need the money.

That cash cushion? It gives you two full years for markets to recover from short-term dips. Historically, that's been plenty of time (more on this here). The bond allocation provides a less volatile buffer for years 2-7. And your stock allocation—the most volatile piece—isn't touched for seven years or more, even though you're actively taking distributions from the portfolio as a whole.

I've seen the relief on clients' faces when they understand this structure. When the market inevitably has a rough patch, they're not panicking about selling stocks at a loss. They know their next two years of expenses are sitting safely in cash, giving their long-term investments time to recover.

It's like having a well-prepared case file. You're not scrambling when the unexpected happens because you've already planned for contingencies.

Any cash beyond this strategic allocation? That's where things get tricky.

Sure, it feels comforting to have a massive cash pile "just in case." But more often than not, this approach will underperform over the long run. It's the financial equivalent of over-preparing for a case that never goes to trial—you've spent time and resources on protection you likely won't need.

Instead, I recommend having a cash management plan that aligns with your actual spending needs and realistic market recovery timelines.

The path forward is clearer than you might think: Start with your expenses to determine what return your portfolio needs to generate. Match that to a historically appropriate asset allocation.

Then build your war chest with 1-2 years of withdrawals in cash.

This isn't about timing markets or predicting the future. It's about creating a structure that lets you sleep well at night while your money continues working for you throughout retirement.

You've spent your career building a practice based on preparation and strategy. Your retirement portfolio deserves the same thoughtful approach.

Financial Advisor